The integrity of our vocational education and training (VET) system rests basically on three pillars: the competency standards, the quality of our training and assessment practices, and the capacity to add value to stakeholders with our training proposal.

Having a regulatory framework is necessary to achieve national consistency and minimum quality standards across our sector to meet stakeholders’ needs and expectations.

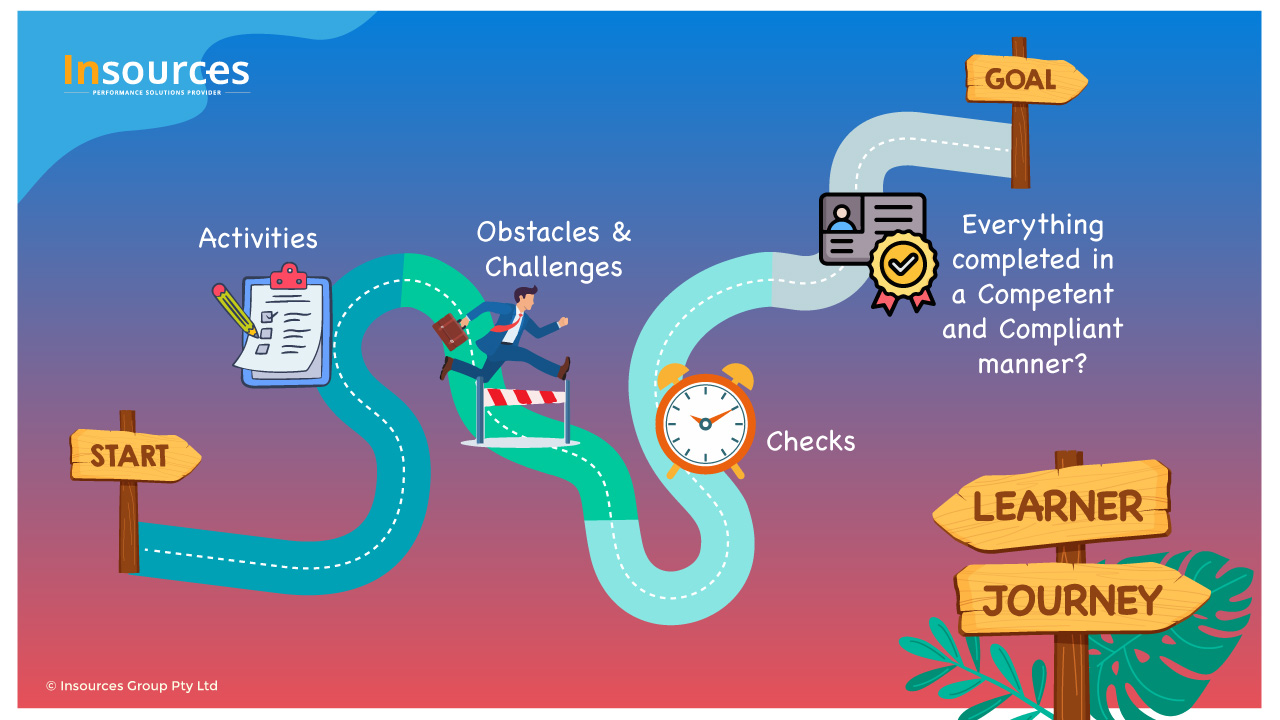

An effective regulatory framework is one where RTOs can understand the outcomes that the system provides, the critical aspects of the process involved in VET, and sets the minimum acceptable standards. Final outcomes of critical points along the complete operation are vital for success, when providing individuals with training services with an employment outcome.

When the regulatory framework does not set those critical points right, there is a risk of a contradiction between the desired outcome: “providing individuals with training services with an employment outcome”, and what the regulation is trying to enforce. In those cases, the cost of compliance with regulation does not add any benefit to the industry and this results in negative value.

Over-regulation or non-effective regulation is affecting our industry, and it is certainly an important area where national consensus of stakeholders and clear vision is imperative to overcome the current VET crisis.

Going back to that system’s pillars mentioned above, I would like to analyse in this article the competency standards we use and the way we communicate them to all stakeholders.

What do we teach in VET?

Competency standards – Qualifications and accredited courses built on fundamental blocks called units of competency.

In other words, we interpret and codify the task(s), in units of competency, that our current workforce is expected to perform. We describe the outcomes of the tasks and the skills, knowledge, and attitudes required to complete the task(s), under certain workplace conditions, and up to certain workplace acceptable standards.

To produce that code (the unit of competency), highly sophisticated skills are required to put in writing a message that will later be interpreted (de-codified) by trainers, assessors, instructional designers, etc.

Considering the process of writing units of competency, I would like to focus the attention on two areas that might not be working well for the system:

- A very technical language (jargon) has been adopted in the description of these competencies. But in most cases, this jargon does not represent the technical language used in the particular workplace/industry where the task is performed.

- The skills required to write units of competency are not part of any qualification, skill set or unit of competency, consequently the content of training packages is inconsistent in both style and quality.

The Registered Training Organisation’s (RTO) interpretation (de-codification), also called unpacking the unit(s) of competency represents a core activity, and the integrity and success of training services provided by the RTO will depend on the quality of this interpretation.

What is the challenge for RTOs?

RTOs must interpret (de-codify, unpack) units of competency first, to understand the task(s) outcomes required, and the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to complete the task(s). Next, the RTO’s job will be to contextualise the general workplace conditions described in the unit of competency to a particular industry sector, or even employer (this will depend on the RTO’s target group).

Once again highly sophisticated skills are required to interpret units of competency, and further contextualisation. While these skills are included in the TAE40110 Certificate IV in Training and Assessment (“… read, analyse and interpret all parts of a unit of competency… …to develop effective applications for the client.”) there are no clear indications about how this critical core process should be carried out.

After several years of experience managing trainers and assessors, I recognise that most of the people that successfully complete the Certificate IV in Training and Assessment have not developed, throughout the course, the skills required to read, analyse and interpret all parts of a unit of competency.

The problem with the delivery of the Certificate IV in Training and Assessment seems to be that while it provides students with “declarative knowledge”, does not train students in the procedural skills require to “read, analyse and interpret all parts of a unit of competency”, nor the strategic skills required to “… develop effective applications for the client”.

This deficit in the delivery/structure of the qualification is magnified when RTOs don’t have clear procedures that guide trainers, assessors, curriculum designers, etc. in reading, analysing, and interpreting units of competency…. …to develop effective applications for the client.

In my opinion, the current regulatory framework (VET Quality Framework) does not effectively regulate the critical core tasks mentioned above. I wonder if at the level of policy makers, there has been enough consideration given to the process we want to regulate, which involves abstracting from a procedural knowledge (performance of tasks in the workplace) and express that in declarative knowledge (units of competency, training package), for RTOs to have as a benchmark to create training and assessment strategies that will translate into procedural knowledge again, in competent and job ready graduates.

The second conclusion I want to share in this article, is a reflection about the way we are using units of competency. There is a lot of room for improvement here if we work together (curriculum writers, policy makers, trainers, VET professionals, Industry Skills Councils, NSSC, Regulators). If we continue working in isolation the results are obvious, we are going in all directions and therefore we are going nowhere.